Srinivasa Sastri, in so far as we have studied him in the foregoing pages, was a man who never could be stereotyped as either this or that type of votary of any particular political ideology or as anyone who could be easily swayed by any extreme notions of Nationalism, Patriotism or Liberalism. And nor was he any inveterate or wholly Hindu Sanatanist, Anti-Sanatana Secularist …. nor any mere Performative Orthodox Brahmin… Sastri never did fit neatly into any pigeon-hole. As many of his vast circle of political colleagues found to their consternation, in the then prevailing political discourse of India and Great Britain, Sastri more often than not seemed a square peg in a round hole.

The question however may be asked:

Judging by how present-day yardsticks are applied to know what is a man’s core political affliation, could it be said that there was a certain furtive streak in Srinivasa Sastri’s that was suggestive he was a Hindutva-vaadin … i.e. a nationalist who teetered almost on the border of jingoistic ‘raashtra-vaada‘?

A pointed question as above, however, would naturally raise indeed a few corrollaries such as the following:

Do Sastri’s professed and practised values of liberalism have any resemblance to those of today’s so-called “Liberals” in India or to the so called grander notions of “neo-liberalism” in the Western world?

If Sastri had been alive today would he have made common cause with those Indian politicians today calling themselves champions of liberal values…. and of the so-called “soul of India” ?

If Sastri were to be living today amongst which side of the “Hindutva-vaada” debate would he have veered towards ?

In a very moving condolence message that she sent to the family of Sastri on his demise, the poetess-patriot, Sarojini Naidu, wrote these famous lines which provide the glimmer of a clue that leads to answers for the questions above. She said:

“He (Sastri) wrote to me long ago (that) “I have lived too long in the shelter of the school-room to be able to adjust myself to the noise of the market-place”. But, although his approach to political problems was somewhat cautious and even conservative, in recent years he seemed to have developed closer sympathy with the more dynamic ideals and programmes of the more actively-nationalist sections of the Indian people.”

There was no doubt that between 1942 and 1946 when he died, Srinivasa Sastri’s innate “cautious conservatism” of spirit and mentality came under severe stress and he found himself on occasions, rare though, when he found himself involuntarily developing, as Sarojini Naidu accuratel put it, “closer sympathy with the more dynamic ideals and programmes of the more actively-nationalist sections of the Indian people.” Only in that limited sense in which the poetess characterised him could it be said that Sastri also tended to lean a bit towards “Hindutva-vaada“.

************

In January 1943, C. Rajagopalachari (Rajaji) had mooted the idea of conceding Pakistan and his canvassing for it began increasing. Although some in the Indian National Congress Party were reluctant to openly endorse the Rajaji’s proposal, support for it from even non-Congress leaders was seen to be muted but not cold.

In January, 1943, the Council of the Servants of India Society, of which Sastri was a long-standing and eminent member, by a majority vote, lent secret support to the partition of India. The Society directed its members to refrain from opposing Rajaji’s idea which it was well known had Gandhi’s blessings and Nehru’s backing . When the Society’s decision and the directive were conveyed to Sastri, who was firmly and fundamentally opposed to the idea of Partition, he felt so shocked and distressed that he forthwith submitted his resignation from the Society.

In his letter of February 27, 1943, to a colleague in the Society, Sastri said:

“I am conscious I am no longer useful or a source of strength to the Society. Age and conformity to old ways of thought make me a relic of a former age! It is as much as I can expect to be tolerated as an object of interest. Time has run rapidly, while I stand still. I realise that I must not become a positive obstruction.

Three months later — during which period while his resignation letter remained unacknowledged by the Society — the Society’s governing body had a rethink on the issue and advised its members of its revised stand on the matter viz.: the Society does not oppose the idea officially but its members are free to express their individual opposition to the idea of Partition and Pakistan.

“I understand (from Chimanlal Setalvad, a jurist and barrister in Bombay), that the President has restored the status quo and allowed members to speak and write against Pakistan if they are so minded. If this be the case, I need not press my application for release. My sense of relief is almost a positive happiness. A tie of thirty-live years, dear to me as life itself, to which I owe all I care for and with which I am identified in the eyes of the world, is not to be snapped. Be sure I am to the Society the same as ever”.

Sastri thus withdrew his resignation from the Society but a gnawing sense of unease he felt now over the looming prospect of the political vivisection of India by the British Government and, moreover, the Indian National Congress under Gandhi and Nehru acquiescing with it too via Rajaji’s proposal, began deeply rankling and disturbing his mind. And that probably was when Sastri’s latent Hindu nationalistic instincts or sentiments got aroused. He just could not digest the idea of India being partitioned to appease the Muslim population and Mohammed Ali Jinnah.

In a passionately worded private letter to Gandhi, Sastri gave voice to his own hurt “national pride”. The words were adulatory of Gandhi but the message was clearly meant to chide. Gandhi was “hero-worshipped” as a “saint” who, Sastri said, “experimented with truth and courage”. The letter was adulatory, yes, but it is difficult to read it today and not miss the veiled sarcasm in the tone of Sastri’s every phrase and line:

“I judge you as a saint who has the gift of seeing the truth and courage to experiment with it — and in the experiment has had more success than most saints so called.

That is why I rejoiced in your enunciation and proclamation of the non-violence doctrine, unadulterated and pure, though the Philistine world jeered. Nor can you put me off by an outburst of your humility and confession of inconsistency, weakness, corruption of the soul and so on. This only exalts you the more in my hero-worshipping mind, making your merits the more lustrous and your blemishes, alas, the more glowing.

I place you along with the philosophers and ethicists of fame. The pursuit of abstract thought and the practice of austerities belong to us in India by heredity. To see you descend on occasions from the heights, I feel bereft of my natural garment, disrobed of my national pride.”

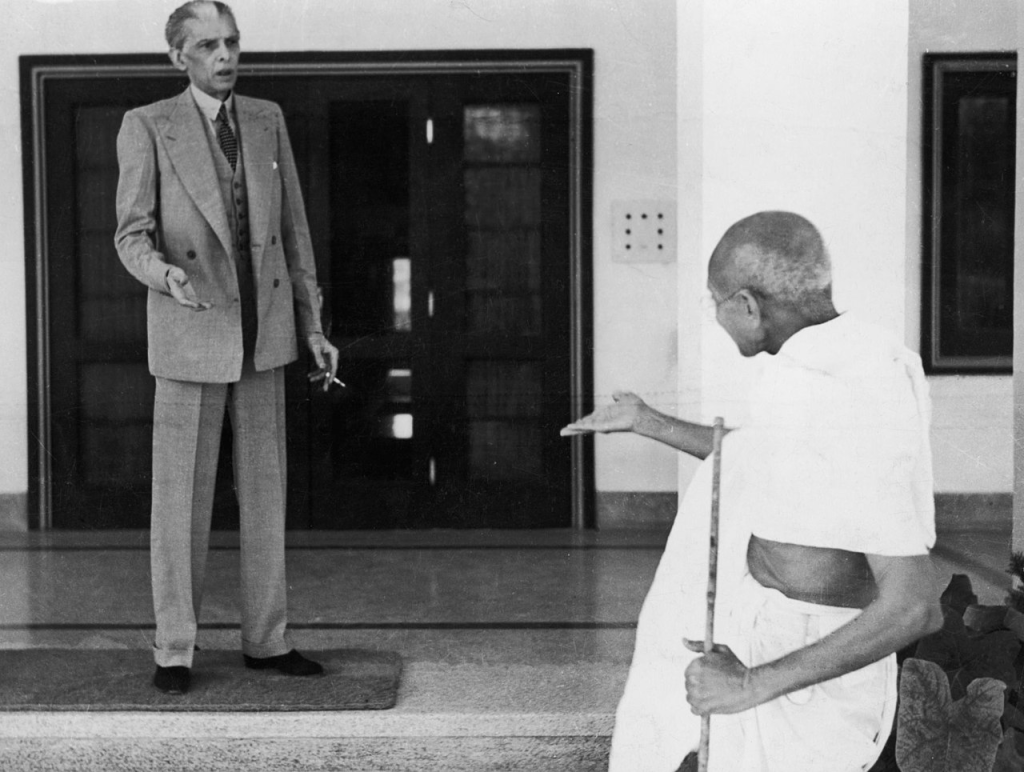

Earlier, in April, 1944, the Mahatma had himself revealed that he had agreed to the principle of the partition of India when Rajagopalachari pressed it on him in 1943. Accordingly, on September 24, 1944, he informed Mohamamed Ali Jinnah the leader of the Indian Muslim League that was demanding a serparate Pakistan, that he would commend Partition, but under certain conditions. Jinnah rejected those conditions outright. Wavell, and even Amery (the British Secretary of State for India in London), felt that the British Government should initiate some steps for Partition and no longer wait on any preliminary communal agreement between the two Indian leaders.

************

In his well-researched biography of Srinivasa Sastri, Kodanda Rao, narrates:

QUOTE:

The news that the Mahatma had agreed to Partition, if only in principle and subject to conditions, created a terrific controversy. The Nationalists were in two minds; they were dead against Partition but at the same time they saw no hope of political advance without it. An increasing number of them felt obliged to concede Pakistan but shrank from (openly) avowing it and took up an attitude of ambiguous neutrality.

Sastri was profoundly disappointed with the Mahatma and perhaps for the first time used a strong expression of disapproval in a personal letter of August 11, 1944, to a colleague.

“Gandhi has sold us. He hates the British Raj so much ho would use any means of ending it. Hates, of course, is my word. G. (Gandhi-ji) will call it by some other name.”

Sastri also wrote to the Mahatma and some others that he was “boiling over and should burst out.”

UNQUOTE

The bitter controversy over the issue of Pakistan and the increasingly frequent talk of “civil war” created alarm in every one’s, including Sastri’s, minds.

It was at that time that the Tej Bahadur Sapru (1875-1949, another freedom fighter who had left the INC to found the Liberal Party of India) who was a leading member of the Hindu Mahasabha, and a close associate of Sastri, proposed a conference of non-Congress Party leaders to find a way out. Sastri was invited to accept the Presidentship of it.

Sastri declined. In his letter of August 25, 1944, to a colleague, he explained his reasons:

“I never had any fight in me. Now I am useless for a warm debate. The other day I suffered during and after a speech so much that I resolved never to go on a platform again. Yesterday, however, I spoke on the same subject for a trifle of a hundred minutes! Repentance holds me at the moment, but I shan’t take an oath.”

In another letter of September 1, 1944 to his colleague, Sastri referred to the conversation he had with Rajagopalachari about Congress Party’s “repentance” and and, at the same time, the Mahatma’s offer to accept Muslim rule! And it was in that very same letter, for perhaps the very first time in his life, that Sastri thought it fit not to conceal what Sarojini Naidu later was able to discern to be his growing “sympathy with the more dynamic ideals and programmes of the more actively-nationalist sections of the Indian people”. Sastri referred to the conversation he had with Rajagopalachari by quoting the hard-core Hindutva-vaadi, militant freedom-fighter and the leader of the Hindu Mahasabha, Veer Damodar Savarkar:

“Have you seen a typewritten statement over Savarkar’s signature? In it he says several things. Two of these are:

The Congress people, now free, recently celebrated a “Repentance Day”!

Gandhi, while in the Aga Khan Palace, sent the Viceroy a letter suggesting that the British Power be transferred to the Muslim League and Jinnah be given a free hand and Gandhi would persuade Congress to accept the Muslim mie.

“Both are true, though Savarkar has twisted the text somewhat. On the sands of the (Marina) beach here, Madras, one evening I asked C.R (Rajaji), who comes there almost daily, whether the letter was true. He confirmed the substance and proceeded to defend it. I lost my temper and, raising my voice, exclaimed that I wholly repudiated it and that it was damned surrender. I got ill and suffered most of the night.

“I believe there are more of those against than there are for Pakistan. Still here, in Madras at all events, the antis won’t come out and give battle, while the other chaps are very vocal. Why is this? A hush has fallen on people, as though a natural phenomenon of terrific power was in progress, and we can only wait for it to do its worst and come to an end. I am feeble, though all afire and daren’t get excited.”

From the correspondence above, it is clear that on the matter of Partition of India for the sake of appeasing the Muslims with a separate Pakistan, Srinivasa Sastri openly found himself with the “more actively-nationalist sections of the Indian people“, namely the “Savarkarites” of those times and of those who in the present are often branded as “Hindutva-vaadis“.

**********

That Sastri — as he himself had admitted in writing, — was simply “boiling over” the fact which he himself had earlier described in damning words viz.: “Gandhi has sold us”…. and that he felt he “should burst out”, clearly reveals the state of his distressed mind at that point of time in history. Also, he was a man devastated by the fast-paced political developments he was witnessing then all around him, all orchestrated and managed by the Indian National Congress under the leadership of Nehru and Rajaji and by the Indian Muslim League under Jinnah … and all which filled Sastri with grim foreboding that they were inevitably leading to a historic disaster in the making — the Partition of India.

The biographer Kodanda Rao writes:

QUOTE

Nevertheless, Sastri (from his home in Mylapore in Madras) kept up a pretty sustained and wholly uncompromising crusade against the partition of India. On October 24, 1945, just about six months befour his death, he along with three other Indian Nationalists, issued a statement on the subject.

“We think it our duty, and the duty of all who share our views, to give expression to our concern and raise a timely warning as to the direction in which we are drifting. None of us is clear as to the precise implications of the two-nation theory.

Much less perhaps are those who advocate it. The country has never been given any precise details of the territorial division of the country and the lines of demarcation between the two Indias. When Mr. Jinnah is asked to define the territorial demarcation, he has always evaded the issue by demanding that, in the first instance, the claim of the two-nation theory should be granted as the basis of any further negotiations. Those of us, therefore, who are definitely opposed to the very idea of breaking up the unity of India suffer under a handicap as we are not in a position to know precisely the nature of Mr. Jinnah’s Pakistan.”

The statement strongly criticised the Mahatma and the Congress for their surrender to the Muslim League.

“No measure and no rapprochement could have been so fatal to the unity of India as the Congress Resolution bearing on the right of self-determination for the federating units and the even more regrettable negotiations which took place a year ago between Mr. Gandhi and the spokesman of the Muslim League.”

***********

It was thus truly a sad, cruelly ironic turn of events in the life of the Rt. Hon’ble Srinivasa Sastry that a moment descended so suddenly and so unexpectedly in his illustrious career as freedom fighter for India when he found himself, an uncompromising Liberal-Humanist of the finest order, being forced by overpowering historical circumstances to have to speak the same sort of language as today’s Hindutva-vaadins….

(to be continued)

Sudarshan Madabushi