Eepa’s unique perspective still did not stop me from persisting in the other more pedestrian question for which too I pressed him for an answer:

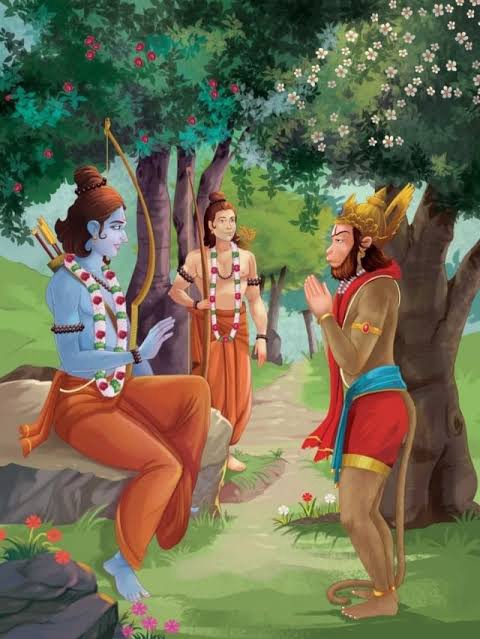

What could have been the language in which Hanuman spoke so impressively that it absolutely captivated Sri Rama ?

“யார் கொலோ இச்சொல்வின் செல்வன்?”

(“Who is this prince of words?”)

In Valmiki’s Ramayana, Hanuman is described as speaking in a language that is both sweet and perfect, with mastery over Vedic knowledge, grammar, and syllabic precision. The Ramayana describes Hanuman as speaking in a “sweet human language” (मधुरं मानवाक्यम्, madhuram manusham vakyam), meaning language of the people, not of elite pundits or archaic Sanskrit. Tamil scholars for many decades now have proposed that “madhuram” here refers not merely to “sweetness” but possibly to a specific spoken language commonly understood across the Kishkinda region (now borderlands of Telengana and Karnataka State) .

There is a strong tradition—especially in Tamil scholarly circles—that Valmiki’s use of “madhuram” alludes to early Tamil or a proto-Tamilic language, reflecting its wide use in Southern and possibly Eastern Deccan region of India at that time.

The theory of these Tamil scholars is that Hanuman did not use Sanskrit, so as not to arouse Rama and Lakshmana’s suspicion, but chose a refined common tongue—characterized variously as “madhura bhasha”, “manusham vakyam”, or “human speech. The pedagogic reasoning is that the phrase “manusham vakyam” contrasts with “deva bhaasha” which means “the language of the gods” — an epithet by which Sanskrit has always been known in all ancient annals of historic and pre-historic India.

The theory therefore is that since Valmiki wrote specifically that Hanuman spoke to Rama in “manusham bhaasham” which was “madhuram” and not in “deva bhaasha“, he must have spoken in Tamil not in Sanskrit. Implicit in such a conclusion is the averment that Sanskrit is not as sweet or “madhuram” as Tamil.

**********

The Tamilian Ramayana punditry has also been fond of further expanding the theory of Hanuman having spoken to not only Rama in the Kishkinda Kandam in some kind of “proto-Tamil” local, indigenous dialect, but that he resorted again to the same language in the Sundara Kandam when he landed secretly in the dark groves of Ashokavana in Lanka to discover where Sita was kept imprisoned by Ravana. This interpretation is once again derived from the “madhura bhaasha” theory of Tamil scholasticism although it relies not on direct scriptural statements, but on literary analysis of how Valmiki describes the speech, the usage of specific proverbs, and interpretations of the language described as “madhuram” (sweet, pleasing).

In the Sundara Kanda, Ashokavana episode, Hanuman repeatedly debates with himself as to which language to use with Sita, fearing that if he speaks in Sanskrit, she will mistrust him and suspect he was some kind of demon trying to trick her, since Sanskrit was the language of the learned and Ravana’s court. (vide Smt. Jayashree Saranathan’s expositions). Narayana Iyengar was a Tamil scholar who, in an article in 1938, claimed that Hanuman spoke to Sita in Tamil by citing as authority Valmiki’s poetic choices and by the identification of a Tamil proverb (“A serpent only recognises the feet of another serpent”) that he stated was embedded in Sita’s speech as a folk saying found only in Tamil tradition, not Sanskrit or Prakrit…. “பாம்பின் கால்களைப் பாம்பே தெரியும்“.

So, it is averred that Hanuman spoke to Sita in Ashokavana only in the Tamil language, or at least in a language closely related to ancient Tamil, when he first conversed with her in Lanka. Many other proponents of the Tamil theory suggest that “madhuram” is not just about “sweetness of speech,” but is an euphemism for an ancient Tamil or Tamilic lingua franca widely spoken in southern and central India, thus possibly the language Hanuman used.

One of the proponents of the theory was, in fact, none other than the venerable 44th Pontiff of the Sri Ahobila Mutt, Srimad Vedanta Desika Yathindra Mahadesikan (“Mukkur Azhagiyasingar”) who too, it is learnt, believed that Hanuman spoke to Sita in a proto-Tamil dialect. Sri Vaishnava orthodoxy thus puts its full weight behind the “madhura bhaasha” theory of proto-Tamil being the preferred language in which Hanuman spoke both to Rama and Sita in the Valmiki Ramayana.

***********

Even in the face of such overwhelmingly formidable scholastic arguments of stalwarts in favour of the “proto-Tamil” argument, I remained skeptical of the theory because, as I messaged back to Eepa, I felt that there was more to explore by way of theorization than making sweeping conclusions in the way Tamil Ramayana scholars have done for so long jumping to them. I shared my candid view with Eepa as follows:

Dear Sir, The term “madhuram” is key … in my humble opinion …

Sweetness , sonority, pleasantness, cadence … all these are characteristics not of Sanskrit or Tamizh which although beauteous in their own way still possess hard harsh guttural sounds … more consonants than vowels …

Telugu is the most soft and languid language of all Sanskritised and / or Tamilised languages and dialects. Every word almost is made to end and sound in a vowel … like “u”, “i” or “a”. The hardest consonant is softened by use of a vowel syllabled suffix … And unlike Tamil there is no difficult retroflex approximant like “zh” in Telugu …

I’d like to believe that Hanuman spoke to Rama in some prehistoric Sanskritised proto-Dravidian local tribal dialect which was perhaps the primordial ancestor of “sundara telungu” — the language that centuries later, was extolled by the great Tamil poet Bharathiyar himself in these soul-stirring words:

சுந்தர தெலுங்கில் பாடும் இசைஞர் துன்பம் இல்லை

அந்த சொல் தென்றல் வாடும் மலரின் வாசம் போல

சொற்கள் யாவும் மலரும், இனிய கீதம் போல.

I had the temerity thus to argue thus with Eepa: Sir, don’t the above lines highlight how Bharathiyar extolled the sweetness and melody of Telugu, comparing its words to fragrant breezes and blooming flowers, and its songs to beautiful, blissful music? So, why not theorise on the basis that the Hanuman spoke in some kind of “proto-Telugu” language to Rama instead of conclusively inferring that it must have been “proto-Tamil” only?

**********

My own analysis as I tried to explain to Eepa was of course largely speculative. But I persisted in putting it forward only to underscore a key linguistic possibility about Hanuman’s speech—one that is still widely debated today but rarely resolved.

Ancient sources describe Hanuman’s speech as “madhuram,” and much hinges upon whether this term indicates specific phonetic qualities, a particular language, or an overarching style valued for sonority and pleasantness. Nothing in the Ramayana text specifies an exact language—only “the human tongue” and “sweet words.” So, everything is only interpretative and nothing can be said to be conclusive.

Telugu’s open-syllable structure and vowel-ending words give it a melodic, vowel-rich, soft sonority unusual among the major classical languages. Early Telugu (pre-literate or proto-stage) was likely shaped by both Dravidian and local Prakrit influences, potentially resembling a widely spoken, accessible lingua franca in the Deccan or southern peninsula. Unlike Tamil, Telugu’s phonology avoids retroflex approximants like “zh,” and the tendency to “soften” consonants with trailing vowels is ancient and distinctive only to Telugu.

Wikipedia, in fact, gives this remarkable clue: “While written Telugu literature emerges on record around 575 CE and florid poetry after 10th c., the spoken dialect must have existed far earlier as a “softened” regional speech amidst harsher Sanskritic/Prakritic or archaic Dravidian forms”.

Linguistic evidence suggests therefore a proto-Dravidian vernacular spoken perhaps widely in South and parts of Central India long before historic Tamil or Telugu literature. Structural features such as retroflexion, vowel harmony, and word-final open syllables are ancient Dravidian innovations—gravitating toward what became the “sweet” quality of later Telugu.

I did however concede to Eepa that my hypothesis—that Hanuman spoke a proto-Telugu/Dravidian-tribal tongue (ancestral to Sundara Telugu), marked by vowel-ending words and mild consonants— might fit mainstream linguistic theory but there is no way I could prove it by any direct textual evidence. That task must be done by Dravidian linguists and well renowned Ramayana scholars.

All that I could say however was only this by way of hypothesising:

While tradition offers Tamil or “common Prakrit” as Hanuman’s language, a strong phonological case can be made for a soft, vowel-rich proto-Dravidian—possibly a precursor to Sundara Telugu—as being “madhuram” in both sound and feeling, aligning with the sonorous linguistic ideals Hanuman displayed.

**********

Eepa in his Whatsapp messages to me emphatically made it clear that he did not support my hypothesis. His support for the “proto-Tamil theory”, he explained to me, was based on a much broader and deeper knowledge of Tamil grammar rather than on any subjective hermeneutics i.e. on notions of “sweetness” or “madhuram” attributed to Hanuman’s speech in Valmiki Ramayana.

He said in his message to me:

Unlike the other Dravidian languages, viz. Kannada Telugu and Malayalam, Tamil grammatical works starting from Tolkappiyam to Nannool, laid down strict rules and regulations how to adopt Sansrit words in Tamil to safeguard its unique identity and structure. This is the reason why the other Dravidian languages were highly Sanskritised but not Tamil. Kamban calls Rishyasingar as “கலைக்கோட்டு மாமுனிவன் “.

Eepa further went on to expand the context of our interesting Whatsapp conversation to the next higher level. He posed further two more questions which also momentarily flummoxed me:

“My query is what could have been the historical reasons for this? What is the reason for Tamil as a language to have been hell bent upon keeping its historical distinctiveness ? Even Alwar poems, as I know them, follow the Tolkappiyam grammatical rules”.

To answer the question adequately, I knew I had to read up more than a bit about Tamil classical literary history since the Sangam times. It was a fascinating subject indeed about which, I confessed, I had never hitherto never given any thought. Eepa was certainly trying to test my own depth in Tamil scholasticism. I told him frankly that I held no pretensions to such in-depth knowledge of the Tolkappiyam to draw from as an answer to his question.

I read up quickly my Encyclopaedia Britannica and a few other sources online too which I generally used as my standard reference sources on any topics related to Tamil literature of the classical kind … such as the Naalayira Divya Prabhandham with which I had at least more than a modicum of close acquaintance.

After my self-taught crash-course in researching the Tolkappiam I was able to answer Eepa’s question by dredging up something as follows. I am not sure however whether it will pass muster with the scholar Eepa.

************

The historical reasons why Tamil grammatical works like Tolkappiyam and Nannool laid down strict rules to regulate Sanskrit word adoption, safeguarding Tamil’s unique identity—unlike Kannada, Telugu, and Malayalam which became more heavily Sanskritized—are rooted in a combination of cultural, political, and linguistic factors:

Tamil Linguistic Identity and Purism

Tamil grammar treatises from ancient times explicitly framed Tamil as a distinct classical language with its own grammar, phonology, and literary tradition, separate from Sanskrit and Indo-Aryan languages. This helped institutionalize Tamil linguistic identity and cultural pride.

These grammatical works prescribed how Sanskrit loanwords should be adapted into Tamil phonetics and morphology to maintain Tamil’s distinctiveness, preserving its native sound system and structure rather than allowing Sanskrit to overwhelm it.

This linguistic purism was motivated by a strong sense of Tamil cultural nationalism already present by the Sangam period, reflected in epics like Cilappatikaram, emphasizing Tamil literature and heritage as unique and superior in its own right.

Historical and Political Context

Tamil cultural nationalism grew as Tamil kingdoms (Cholas, Pandyas, Cheras) consolidated power, fostering a sense of regional pride and identity distinct from northern Sanskritic influence.

Tamil’s relative isolation in the south also protected it from some direct cultural imposition, allowing sustained development of a robust literary ecosystem in Tamil without wholesale adoption of Sanskrit grammar and vocabulary.

Sanskritization did influence royal courts and religious practices, but Tamil literary scholars and grammarians often moderated Sanskrit influence on poetic and grammatical norms to retain Tamil’s autonomy and purity.

Contrast with Other Dravidian Languages

Kannada, Telugu, and Malayalam experienced more extensive Sanskritization due to stronger and earlier interactions with Sanskritic and Brahmanical culture, including religious and royal patronage, facilitating greater lexical and phonological borrowing.

Their literary traditions began developing later and with more direct Sanskrit influence; thus, these languages integrated Sanskrit more freely, lacking the early linguistic purism framework that Tamil had established.

Kamban’s Epithet for Rishyashringa

The phrase ‘கலைக்கோட்டு மாமுனிவன்’ used by Kamban reflects Tamil’s reverence for learned sages who master arts and knowledge but also implicitly reinforces the Tamil ideal of scholarly purity and guardianship over Tamil tradition, contrasting with excessive Sanskritization.

It symbolizes Tamil’s balance between open yet cautious acceptance of Sanskritic elements, ensuring that Tamil’s core identity remained unsullied and sovereign in the literary and cultural realm.

Tamil’s resistance to heavy Sanskritization lie in its robust early grammar tradition, strong regional cultural identity, and conscious linguistic purism that framed Sanskrit borrowings as something to be adapted delicately. This contrasts with other Dravidian languages whose later literary emergence and sociopolitical contexts favored deeper Sanskrit integration

**********

My quick and rough research dive into this subject of Tamil Resistance to Sanskritization over the ages helped me to grasp one other important finding which I had never in the past bothered ever to inquire:

Which historical periods saw active de-Sanskritisation efforts in Tamil?

While, historically, it was linguistic purism which motivated a strong sense of Tamil cultural nationalism already present since even the pre-Sangam period, and which emphasized Tamil literature and heritage as unique and superior in its own right, that pride was never chauvinistic or parochial; nor was it rabidly xenophobic as we know it to be today in the State of Tamil Nadu. De-Sanskritization in the period before the later part of the 20th century CE was about Pride whereas in the post-1950s period it was all not about Tamil Pride but about anti-Sanskrit or anti-Hindi.

Post-Independence 1950s onwards: The most prominent phase of active de-Sanskritisation in Tamil occurred during this time by followers of Dravidianism. Leaders and intellectuals consciously promoted the use of “pure Tamil” (taṇittamiḻ) by removing Sanskrit loanwords and focusing on native Tamil vocabulary especially in formal documents, literature, education, and public speeches.

Late 19th to early 20th century: While Sanskrit influence was still prevalent, the seeds of language purism and resistance to Sanskritization emerged among Tamil scholars and reformers, setting the stage for later systematic efforts.

Medieval Period (11th to 13th centuries): Although Sanskrit vocabulary entered Tamil during this period, literary and religious Tamil texts retained a considerable degree of linguistic self-regulation. Tamil poets like Kamban celebrated Tamil literary traditions while acknowledging Sanskrit epics indirectly, helping preserve Tamil’s distinct identity

All the above movements were a response to the heavy Sanskritization seen in other Dravidian languages (Telugu, Kannada, Malayalam) and aimed to protect Tamil’s unique classical heritage. The result was a perceptible decline in the Sanskrit loanwords in Tamil literature and formal use—from estimates of 40-50% down to about 20% in the 20th century and beyond.

**********

My exchange with Eepa ended there with the the unasked, unanswered and unthinkable question: By de-Sanskritizing Tamil language, did Sanskrit lose or did Tamil lose linguistic “praana” — life-force ( प्राण) — or the vitality which in Tamil is called “uyir”, (உயிர்)?

Sudarshan Madabushi