It is only very late in my life today, and I regret to say it, that I have received the Grace of Bhagavan to embark finally upon a serious study of the Rahasyatrayasaram in the traditional learning mode of “grantha kaalakshepam” under an erudite Sri Vaishnava scholar-Acharya.

Because of ageing factor and also the lack of ease of my acquaintance with Manipravala texts, I have found it a little difficult at times to internalise the profundities of doctrine expounded in the Rahasyatrayasaram. The tutoring by my Acharya no doubt follows closely the scriptural text faithfully and, yes, many of the passages in it that reveal concepts such as “artha panchaka” in it do come alive so vividly and with greatly enlightening meaning when explained so well. Nonetheless, there are occasions, when I do find myself stumbling and grappling with the real essence of what is imparted.

On such occasions of relative incomprehension or confusion, arising from my personal indequacies, I often do find myself beginning to muse, with the aid of a bit of “lateral thinking” technique, over that which escapes deep understanding. Edward de Bono (1967: a Maltese psychologist) described the technique of “Lateral Thinking” as “a structured approach for thinking differently“.

With the background and approach of someone who had spent most of my professional life in the contemporary corporate world for several years, in trying to fully understand the doctrine of “artha panchaka“, I knew in my heart that I was always going to be a tad predisposed towards trying to come to terms with the doctrine using the technique of “lateral thinking” — something I had learned before as part of my career higher-education. Therefore, I began mentally to attempt mapping the 5 elements of the “artha panchakam” onto what in the corporate world is called a SWOT-grid… the acronym SWOT standing for “Strength, Weakness, Opportunities, Threats”. It was not that any sudden urge of perverse or maverick thinking which drove me to do so… It was only earnest desire, in fact, “to go from the known to the unknown”…

**********

Most of us who have worked in the corporate or business environment, I am sure, already know what SWOT is; nonethless, here below is just a brief recapitulation of the concept and practice.

SWOT analysis is a strategic planning framework used in corporate strategizing to evaluate an organization’s internal strengths and weaknesses alongside external opportunities and threats, enabling informed decision-making and competitive positioning. It supports initial planning stages for business decisions, product launches, or market entry by fostering holistic insights and action plans. SWOT analysis is commonly used in business situations (brainstorming etc.) requiring strategic assessment of internal capabilities and external environments, such as developing new strategies, launching products, or entering markets

Threats: External risks including competition, economic shifts, or supply chain disruptions that could undermine success.

Strengths: Internal attributes like strong brand presence, skilled workforce, or efficient operations that provide competitive edges.

Weaknesses: Internal limitations such as inadequate resources, poor processes, or skill gaps that hinder performance.

Opportunities: External factors like market trends, technological advances, or regulatory changes that can be exploited for growth.

SWOT-grid or matrix is typically represented as a 2×2 grid categorizing internal and external factors.

************

The line of reasoning or thought-process that led me to believe mapping the 5 elements of the “artha panchaka” to the SWOT grid made a wee bit of sense was this:

Just as it is important in the world of business to “introspect” upon strengths and weaknesses to be able to “assess” the grid of opportunities and threats before it, in much the same way, the artha-panchaka too offered a similar “framework” of spiritual introspection in the profounder context of Sri Vaishnava soteriology. For the purpose of making the connection of similarity, I thought it appropriate to associate Weakness with Jivatma svarupa; Opportunity with the Upaya svarupa; Threat with the Virodhi-svarupa; Strength with the Paramatma svarupa… and finally, the Phala-svarupa’s association with what in corporate parlance is always recognized as Mission Accomplishment.

***********

As I began to muse and mull more deeply upon the mapping of the two concepts inside my mind — one a profoundly Vedantic idea and the other a run-of-the-mill corporate practice — I gradually began to realise that it was quite a helpful exercise to do mentally but then only as a pedagogical and introspective device, provided however, that I kept its limits clearly in view. In other words, it began to sink into me that the mapping might work only partially but would not serve the full purpose of internalizing the “artha panchaka” doctrine fully.

- Treating jīvātma-svarūpa as “weakness” makes sense in so far as the jīva, left to itself, is dependent, finite, and vulnerable to bondage and error; the whole need for upāya arises from this existential “inadequacy”.

- Paramātma-svarūpa as “strength” also resonates: the only real resource in the system is the Lord’s omnipotence, auspicious qualities, and gracious will,on which the aspirant’s hope strategically rests.

- Upāya-svarūpa as “opportunity” fits the idea that the Lord has opened a gracious path (especially prapatti) that the jīva can avail, a divinely provided “strategic option” that changes the jīva’s otherwise bleak situation.

- Virodhi-svarūpa as “threat” is almost exact: Desika’s enumeration of internal and external impediments functions structurally like a risk-register which must be recognized, monitored, and mitigated.

- Phala-svarūpa as “mission accomplished” mirrors the idea of a clearly defined end‑state: nitya‑kainkarya in Śrī Vaikuṇṭha, with all intermediate metrics (various sādhana‑states) subordinated to that telos.

- In SWOT, strengths and weaknesses are “internal” factors to the firm, while opportunities and threats are “external”; in Artha‑pañcaka, all five artha‑s are objects of true knowledge, not simply factors to be leveraged in a strategy the jīva designs.

- Most crucially, the core logic of Śrīvaiṣṇava soteriology is not optimization of one’s own capabilities but relinquishment of self-reliance in favour of sole reliance on divine grace; this decisively undercuts any reading that treats Artha‑pañcaka as a self‑help technique in corporate style.

- For someone trained in corporate strategy, using a SWOT‑like grid can sharpen attention to the relational structure: “I, as dependent self, face real virodhi‑s; my only ‘strength’ is actually His strength, accessed through the divinely given upāya, for the sake of a clearly defined puruṣārtha.”

- As long as the analogy is kept consciously provisional and is periodically checked back against the primary categories (sva, para, upāya, puruṣārtha, virodhi) in the text, it can serve as exactly what you call it: a tool‑kit for self‑introspection, not a replacement frame that domesticates the theology into secular management theory.

The mapping of the SWOT GRID to the Doctrine of “artha panchaka” thus has useful but only limited utility and value. It can certainly be quite helpful as a pedagogical and introspective device, provided its limits are kept clearly in view always. It should be always treated as a crutch … a wobbly “walking stick”… that can only help one maybe to heave oneself up intellectually in coming to grips with the doctrine… but which must be abandoned and thrown away as soon as one is fit to stand erect and — with the guidance of one’s “kaalakshepa Acharya” — walk steadily into the realm of internalising “artha-panchaka” not simply as abstact doctrine but as a lived, spiritual experience.

**********

Since modern conceptual tool-kits such as the SWOT etc.. fail to effectively serve as conceptual frameworks to studying Visishtadavaita soteriology, the only fail-safe alternative for a seeker is to study devotional texts in Sanskrit and Tamil.

Traditional hermeneutic frameworks from Hindu theology, such as Vedic śāstric exegesis (tātparya-niyamaktea-lakṣaṇās), offer robust alternatives to business or other modern models for studying devotional texts like Rahasyatrayasāram, since they emphasize layered meanings over so-called “strategic analysis“.

The more practical contemplative tools for understanding the doctrine of “artha-panchaka” would be “kaalakshepam” mode of learning. During “kaalapshepam” sessions, deeper and contemplative content analysis of the doctrine becomes possible. What helps greatly in the process is the study of Upanishad parables, the Āḻvār bhakthi hymns or even the dialectical maṇḍala-mapping (circling core truths like paramātma around jīvātma) — all of which foster internalization of “artha panchaka” without secular distortion. This is the unique feature, in fact, that is seen in the guru-śiṣya paramparā method of study. The method safeguards the sacred text’s anti-autonomous thrust since it invites “surrender over strategy“.

Narrative theology woven during “kaalakshepam” sessions thus effectively reconstructs doctrinal stories forming “artha” soteriological arcs, while the hermeneutic content analysis (vyaakhyaana) identifies recurring motifs like virodhi-obstacles qualitatively. All these go to foster truly immersive understanding of Grace-centric themes, avoiding SWOT’s instrumentalism.

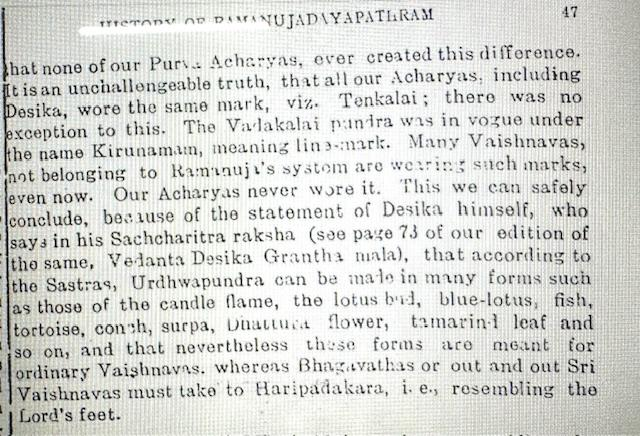

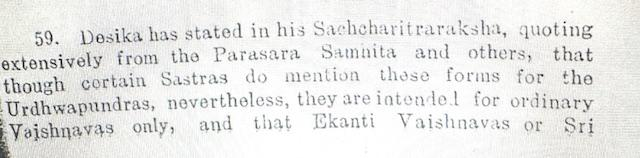

Swami Vedānta Deśika’s own tradition employs samaṃvaya (coherence-harmonization), arthavāda (contextual praise), and rahasya-vyākhyāna (esoteric unpacking of mantras) to integrate ontology, devotion, and praxis without reducing them to manipulable factors. He clearly prioritizes śabda-prāmāṇya (scriptural authority) and bhakti-rasa (devotional savoring), revealing Artha-pañcaka as a relational disclosure rather than anything like what the modern (or corporate) mind might view through the lens of a SWOT grid.

Swami Desikan’s core method involves layered interpretation of sacred texts through historical-critical analysis, reader-response, and doctrinal lenses, uncovering contextual meanings without reducing them to intellectual factors or construcgts. In the context of Visishtadvaita soteriology, Rahasyatrayasāram applies tātparya (intentionality) and lakṣaṇā (implication) to reveal relational truths such as śeṣa-śeṣi bhaava without imposing external grids. The RTS thus focuses on the essence of pure religious experience, such as bhakti-rasa or prapatti-surrender, as they appear in higher human consciousness.

Applied to Sri Vedānta Deśika’s classic work, we see that what constitutes the central aim of the RTS is to examine the jīvātma-paramātma dynamics — expounded long before him by his own Acharya, Bhagavath Sri Ramanujacharya — more as a lived dependence rather than “weakness-strength” binaries of the human existential condition.

(Concluded)

Sudarshan Madabushi