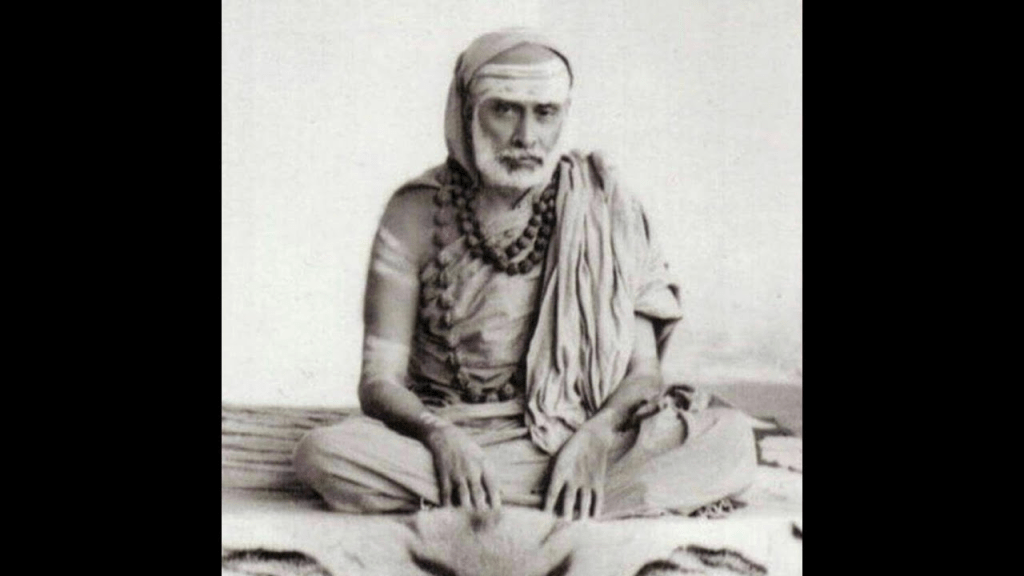

The last days of Srinivasa Sastri were spent in his home “Swaagatham” in Mylapore, Madras… in one of the oldest, most historically well-known quarters of the city (now known as Chennai).

Mylapore was indeed one of the oldest and culturally richest parts of Madras, known for its temples, classical music, and Tamil and Sanskrit scholarship. Sastri, a scholar deeply versed in Sanskrit, Tamil, and Indian traditions, found in Mylapore a vibrant and spiritually salubrious environment since it greatly nurtured his love for classical learning, religious harmony, and cultural continuity…. all his core liberal values in life.

Mylapore was also home to many of his close and dear friends and contemporaries in the Brahmin intellectual and political elite, often called the “Mylapore Clique,” who were known for their scholarly pursuits and contribution to the Indian National Freedom movement. They all had like Sastri embraced the politics of moderation and constitutional methods.

Sastri’s own residence and work were both closely linked to this Mylapore cultural milieu, which influenced his sense of identity and intellectual pursuits. The rich temple traditions, festivals, and cultural activities of Mylapore embodied the same “Sanatana Dharma” values that Sastri so deeply respected and avidly promoted.

Mylapore was a place where classical Carnatic music, literature, and religious discussions thrived, of which all Sastri, a patron himself, supported through his engagements with scholars, poets, and institutions. The influence of Mylapore provided a conducive cultural grounding for Sastri’s approach to nationalism and gradualist reform, blending respect for tradition with modern education and civic values. Here is how he felt about his own home in Mylapore:

“In the sacred streets of Mylapore, where temples and scholars alike rise in enduring testament to our culture, lies a living testament to India’s spiritual and intellectual heritage. This ambience nurtures not only faith but reason; it inspires us to pursue knowledge with humility and serve with diligence.”…. “Let us remember, in these sacred environs where poetry and song ring out, that the work of the mind and the work of the spirit go hand in hand. Mylapore and her scholars gift us this example, and we should cherish it as a beacon for all India.”

Mylapore in Sastri’s time, as it is even today, was famed for its religious ambience and grand landmark temples… the Kapaleeshwara Temple being the most magnificent of them all. Sastri was a man of both Reason and Faith at the same time and he found it easy to soak and luxuriate himself in that ambience…. It was truly la dolce vita of Mylapore! Kodanda Rao, Sastri’s biographer’s quote below reveals the religious side of the man:

QUOTE: The doctrine of Bhakti, as revealed in the Gita, captivated his (Sastri’s) heart, but not his head. Sastri said: “The struggle between the head and the heart, described with self-revelatory pathos in religious writings, rages perpetually within me. It is only my lifelong practice of self-control that cloaks the gnawings of my inmost being behind a blank expression of face.” He craved for some experience, some revelation, some authentic sign of life after death. He had moments when he preferred the contentment of the pig in the sty to the agitation and turmoil of the enquiring mind. But he soon found consolation and encouragement in the thesis that “there is more faith in honest doubt than in half the creeds” and concluded that to believe what was not proven to one’s satisfaction was to abdicate the sovereign quality of reason. UNQUOTE

Sastri himself did like to go on occasions to worship in temples since he regarded “The temple is not merely a place of ritual; it is a center of art, philosophy, and community. The centuries-old traditions of Mylapore have taught me that our past is not to be preserved as a museum but lived as a fountain of inspiration for modern progress.”

Sastri’s house in Mylapore thus became a beehive of cultural activity and a watering-hole for neighbourhood cognoscenti. The home called “Swaagatham” became known for being an informal gathering spot for intellectuals, where figures from different disciplines—poetry, politics, philosophy—met for lively, spirited discussions.

“At irregular intervals, a small group of persons interested in public affairs would assemble at Sastri’s home in Mylapore. Sastri would listen thoughtfully, speaking only occasionally but with great weight and precision. His calm deliberations often steered conversations towards reason and reconciliation.”

***********

In his last days in Mylapore, Sastri’s engagement with politics and world affairs was reduced to a bare minimum. Even amongst friends who gathered at his house for intellectual conversations with him, he spoke more on literary, art, music and cultural topics than politics. However, there were two specific matters that did catch Sastri’s attention and on which he did make known his mind. On one matter his comments went public because it concerned an international issue. The other matter which was a local issue, he chose to make his comments private.

The first issue was the advent of the (A) Apartheid Regime in South Africa and the second matter was the emerging (B) Dravidian Movement of the Justice Party of Tamil Nadu led by E.V.Ramaswamy Naicker (aka “periyaar“).

As mentioned (already in an earlier chapter in this series) while he had served in South Africa as Agent-General for the British Government of India, Sastri had recognized the plight of the Indian community there that was being deprived of even basic human and civil rights. The plight was an incipient symptom of the growing racial problem in that country. Even as early as 1927–1929, Sastri had already been acutely aware of the plight faced by the Indian community under white minority rule and he had consistently advocated for their upliftment and equal treatment. He strongly opposed policies treating Indians as aliens or pushing for their repatriation, calling instead for improvements in housing, sanitation, education, and legal status.

Though the formal system of apartheid was officially instituted only after Sastri’s time in South Africa, his diplomatic efforts and public statements condemned the sort of racial segregation and legal discrimination that was driving force behind apartheid ideology. He had worked tirelessly to negotiate better rights for Indians and opposed any legislation that legitimized racial inequality. Now, from Mylapore, he spoke publicly to condemn Apartheid Rule in South Africa in a manner reminiscent of an impassioned speech on Legal and Civic Rights, he had given once in the past:

“It is neither justice nor reason to treat the Indian community as aliens in a land that many of us have called home for generations. The laws that seek to exclude us, to restrict us, to repatriate us, are unjust and must be resisted by all means consistent with constitutional dignity. We reject every form of racial segregation, and we demand the recognition of equal rights before the law.”

The speech directly condemned the nascent apartheid structure of racial segregation and exclusionary laws, calling for equal legal rights.

(B) Sastri’s political career peaked in the decades before the Dravidian Movement became a dominant force in Tamil Nadu. By the time the Self-Respect Movement gathered momentum in the late 1920s and 1930s—and especially when Dravidar Kazhagam (DK) emerged in the 1940s—Sastri was already an aging figure, focused solely on constitutional advocacy, diplomacy, and liberal reform. He spent some of his later years deeply involved in public education, language debates, and literary activity, rather than frontline political activism in either India or in what became later the State of Tamil Nadu.

The Dravidian Movement was openly critical of both the “Hindu orthodoxy” and “nationalist” positions, seeing both as protecting Brahminical privilege and Sanskritic traditions. Periyar’s activism aimed thus to counteract what he saw as Brahmin superiority promoted by Congress moderates, including leaders like Sastri and Alladi Krishnaswami Aiyer.

The main documented response of the liberal Brahmin elite (such as Sastri and Sivasamy Iyer) towards the Dravidian and anti-Brahmin movements was one of disapproval and quiet reservation, often articulated in private correspondence or moderate platforms rather than combative public debate. There are secondary references in the Dravidian Movement literature to “Brahmin leaders“, including Srinivasa Sastri, upholding social separation and traditional values, which Periyar and the Dravidian ideologues criticized vehemently. Mahatma Gandhi himself recognized the parochial and casteist underpinnings of Periyar’s Self-Respect Movement and expressed his alarm at the spectre of narrow, sub-national “identity politics” beginning to loom large in the State of Madras:

“The Justice Party… opposed Brahmins in civil service and politics, and this anti-Brahmin attitude shaped many of its ideas and policies… Gandhi responded by highlighting his appreciation of Brahmin contribution to Hinduism and said, ‘I warn the correspondents against separating the Dravidian south from Aryan north. The India today is a blend not only of two, but of many other cultures.'”

Sastri and his Mylaporean colleagues like Alladi Krishnaswami Aiyer and Sivasami Iyer represented traditional Brahminical values in their public comportment, moral philosophy, and literary emphasis—which stood in implicit, if not explicit, contrast to the Dravidian critique. They came to symbolize—for critics and Dravidian polemicists—an older establishment whose influence was now being actively challenged, not so much in direct confrontation, but through structural social shifts and new populist mobilisations in the streets and public squares.

From his home in Mylapore, which was itself witnessing the winds of change in its traditional and cultural ethos from liberalism to increasing Tamil parochialism, Sastri might have silently brooded over his foreboding of a grim future for the Tamils of Madras State —- a future where Periyar’s “movement would not work out too well for the Brahmin who would be made the scapegoat for 500 years of Tamil decline slowly unfolding itself…

Sastri sensed that the earliest manifestations of the Dravidian movement was not particularly rabid or secessionistic but was more focused on resentment of Brahmin ascendance, particularly in provincial government and education. Yet he feared that the Movement had in it seeds of secessionism.

Sastri did not however personally engage in any documented direct commentary or confrontation with E.V. Ramaswamy Naicker or the Dravidian Movement. His moderate, liberal reformism and devotion to Sanskritic culture stood in intellectual opposition to the radical anti-Brahmin politics of Periyar, but their interaction was one of contrast, not direct conflict or debate.

**********

In the years and decades to come, the ethos of cultural and intellectual excellence of Sastri’s beloved Mylapore would surely undergo a sea-change. It would be able to neither resist nor overcome the ideological onslaught the Dravidian Movement would come to inflict upon the so-called “brahminical” social order and its values of liberalism that Sastri and his “Mylapore Clique” had espoused and wished to propagate.

Inevitably, the time to depart from such a fast crumbling old world order waa fast approaching… Sastri’s angina pectoris attacks were becoming more and more frequent and ominously unbearable too…

(to be continued)

Sudarshan Madabushi