Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, the mass leaders of the Indian National Congress who were at the forefront of the Freedom Struggle against British Colonial Rule all fell into roughly three broad but clear ideological groupings. They were all patriots devoted to the cause of Independence but they differed sometimes quite widely in their respective approach towards how the struggle must be waged. The end was one but the means were varied.

In that broad spectrum of freedom fighters, at one extreme were arrayed those like Veer Savarkar, Bhagath Singh and Subhas Chandra Bose, to name only a few, who made no secret of their choice to take up arms against the British Governement in India. At the other end of the spectrum were those aligned with Gandhi’s non-violent satyagraha approach — which included ceaseless agitation against the British Government in the form of Civil Disobedience, and Non-Cooperation movements. Straddling the movement in the middle between the two extremities of the spectrum stood those who adopted the old-school Gokhale-Ranade methods of “gradualism” that sought freedom from the British by pressing home their advantage not through overly agitational or revolutionary methods but by exploiting the imperial Britain’s own inherent sense of justice and fair-play, “constitutionalism” and much-touted “liberal-humanist” (Fabian social-democracy) values and “civilisational ethics“.

************

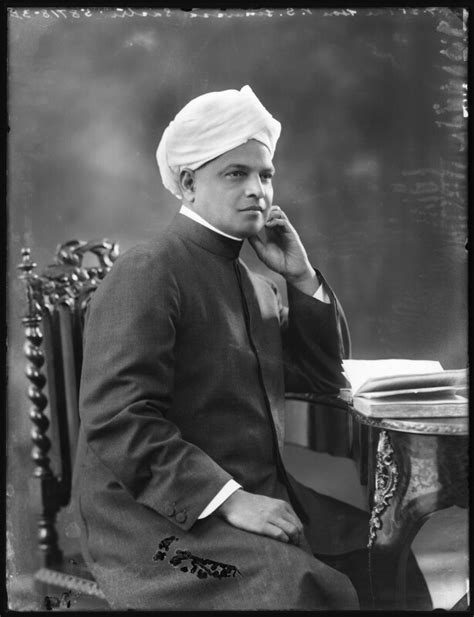

Srinivasa Sastri belonged to this third group. Although he and Gandhi differed in their choice and paths of political activism — in that classic moral binary where the End clashes with Means — the astute judge of men’s innate talents that Mahatma Gandhi was made him recognize and skillfully commission and deploy Sastri’s many versatile skills and capabilities to further his own goals.

Gandhi returned for good to India in the early 1920s after having spent many years working for the rights and freedoms of the indentured Indian-community there. It was in South Africa that his “experiments with truth” and the methods of “satyagraha” had been put into practise and then honed and developed into a powerful weapon of non-violent political agitation. Gandhi was all set then to unleash that weapon in India too against British Imperial rule and for Independence.

The British Government in India was acutely aware of the danger of Gandhi’s Satyagraha mass-movement strategem getting exported from India to South Africa and fomenting there in that country the same Civil Disobedience and Non-Cooperation movements which were gathering steam at home under the auspices of the Gandhi-led Indian National Congress. The virus of Satyagraha, the British were convinced, if it did spread to South Africa too, it would very likely lead to a sort of cross-border consolidation or coalition of freedom-fighters in both India and South African Indians. That would cause a potential cross-continental political crisis for the British Crown that was already tottering from the ravages of the First World War and inevitably lurching towards the Second at that time.

Gandhi was acutely aware of the many deep dangers of such a virus spreading from colonial India to colonial South Africa. Although sympathetic to the almost slavish condition of the Indian community in Durban, Natal and Pretoria provinces that the apartheid regime in South Africa had ruthlessly imposed upon it, Gandhi nonetheless realised that that the general demographic, political and social environment of South Africa was not not same as in India.

With intimate, first-hand knowledge of the South African Indian-community gained during his years when he practised as an activist-lawyer there, Gandhi knew that the community was not yet ready for mass Sathyagraha movement. It would be too early and too potentially self-destrutive for Indians in South Africa to confront and take head-on the might of British Rule employing the sort of methods that Gandhi had launched and set in motion in India. The reason why he felt so was because of the generally poor level and standards of education and awareness amongst them of law, constitution, political and civil-rights.

Also, Gandhi’s own unerring sense of the trajectories and outcomes of mass political movements warned him that if a crisis were to explode amongst Indians in South Africa, it was sure to severely affect the course, the momentum and prospects of success of India’s freedom struggles at home against the British.

************

So, under such overarching circumstances, Gandhi and the Indian National Congress (INC) were compelled to tacitly support the British Crown and Government in India in its efforts to put the lid on and contain any potential political movements of freedom such as mass Sathyagraha or Civil Unrest breaking out in South Africa.

The British thus used very ingenious diplomacy to persuade Gandhi and INC to be sort of “ambassadors-at-large” in South Africa to dissuade the Indian community from pursuing any sort of political activism against British Rule, and instead focus more on the greater goal of amelioration of its overall social, educational and economic plight.

Thus, did the leadership of the INC enter into a sort of unwritten pact under which Gandhi would himself undertake to carry out the very delicate diplomatic and international task of mediation and conciliation between the Crown and its Indian subjects in South Africa.

To put the entire matter in broad historical perspective and to describe in a nutshell exactly what the British Goverment of India did, one may use the Tamil idiom: “முள்ளை கொண்டு முள்ளை எடுத்தல்” (“Mullai kondu mullai eduththal“). In other words, the delicate diplomacy the British used to diffuse the potentially crisis-situation likely to break out in South Africa was to skillfully enlist the Mahatma himself to handle the assignment of persuading the Indian community to forsake — at least for the time being then — any idea or program of freedom struggle against the British that was being contemplated and instead to focus more on its own economic betterment and social development.

Mahatma Gandhi was caught in a bind. On one hand, he knew he had no choice but to accede to the British Goverment’s wishes. On the other hand, he also knew that he himself could not go to South Africa to carry out the diplomatic mission since he and the INC were already committed to the freedom struggle movement in India. If he left India to return to South Africa it would severely cripple and compromise the freedom struggle the INC was waging against the Bristish at home.

Gandhi thus looked around for a workaround and it was then that he immediately recognized that the job of carrying out such a delicate international diplomacy entrusted to him by the Colonial Rulers had to be delegated to someone admirably qualified for it. And Gandhi did not have to look too far and wide in India to recruit such a person.

It had to be the eminent Srinivasa Sastri !

Gandhi thus put aside all his ideological differences with Sastri and persuaded him to take up the assignment to go Durban as the emissary de jure of not only the Government of India but de facto, as his very own personal one!

************

Gandhi’s insistence that Sastri go to South Africa to represent Indian interests abroad highlights how Gandhi valued Sastri’s stature and language skills as critical assets in international advocacy. Gandhi’s political strategy increasingly incorporated appeals to British public opinion and international bodies.

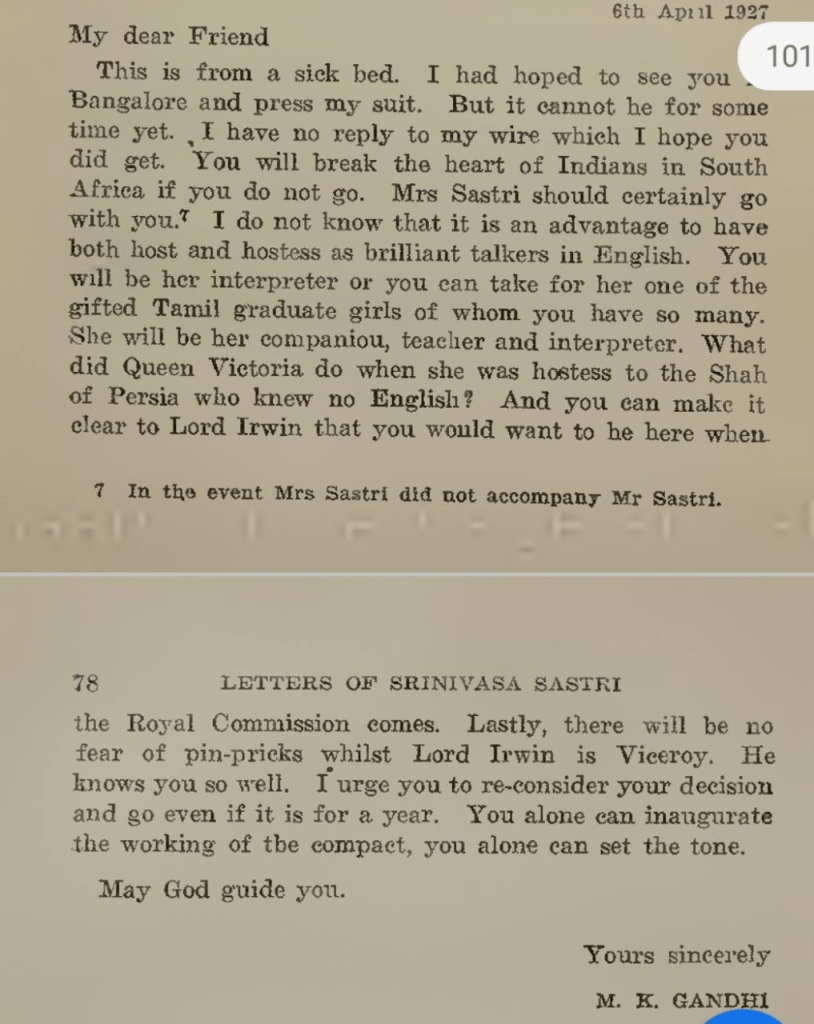

Sastri’s role symbolized this strategy of engaging colonial authorities through persuasion and legal arguments, complementing Gandhi’s mass mobilization at home. The letter that was written on April 6, 1927 shows Gandhi’s recognition of Sastri’s personal integrity, educational background, and ability to act as an interpreter or mediator. Gandhi’s approach often involved aligning himself with respected intellectual figures like Sastri to lend moral and intellectual weight to the independence movement, balancing popular agitation with respectable leadership.

Sastri was known for his deep knowledge of constitutional law, diplomacy, and his eloquence in English. Gandhi’s letter reflects respect for Sastri’s calm, reasoned approach and his ability to represent Indian interests effectively in official and international settings. This likely influenced Gandhi’s strategic use of constitutional dialogue alongside mass civil disobedience, balancing confrontation with negotiation. It was no surprise that Gandhi’s choice of Sastri to be the man for the assignment was influenced Gandhi knowing that Sastri respected constitutionalism, diplomacy, and the importance of international advocacy within the Indian independence movement.

Sastri’s intellectual rigor and polished public persona thus would only complement Gandhi’s mass-based activism, leading to a multi-pronged political strategy that combined moral suasion with direct action.

There can be no doubt thus that it was Srinivasa Sastri who indeed did help Gandhi to broaden the nationalist movement’s reach and impact during the critical phases of the freedom struggle in the 1920-early 1930s.

***********

In South Africa, Srinivasa Sastry handled the truly unenviable task of walking an extremely tight rope of diplomacy, having to represent both the British Imperial Goverment of India as well as Mahatma Gandhi and furthermore, at the same time, also work to advance the interests of the Indian community at large.

Sastri was acutely aware of the perilous assignment he was about to carry out. He was sent to South Africa to act as bridge between a disenfranchised, disempowered, impoverished Indian community and the British Colonial Establishment.

The Indians were disenchanted with the same Colonial Rulers whose representative, ironically, Sastri was! He was also acutely aware that the Indian community would be only to easily prone to compare and pass judgment upon the work he did for them and their causes with the sterling work they had in earlier years witnessed Mahatma Gandhi accomplish.

In a very candid speech that he made to a gathering of Indians in Durban, Sastri was not afraid to be open and honest in laying bare the precarious nature of his assignment:

I will speak about my own mission. As you are aware, I am the first official representative of India in this sub-continent. What led to the creation of the office is within the full experience and knowledge of nearly all of you. But I may be allowed to take you behind the Cape-town Agreement, just to dwell for a moment on the anxieties and fears with which the Government of India and the Imperial Cabinet of Great Britain had always viewed the situation created by the circumstances in which Indians were living in this country, and generally in the Dominions of Britain abroad.

I do not wish to say anything that may be unpleasant or anything that may be in the nature of recrimination. My purpose is not to make matters worse but to make them better, and if I recall the condition and anxieties and fears prevalent among the Government and the people in one common state. If I dwell upon this aspect of the subject, it is merely to show that the Government of India, in handling an extremely difficult and delicate situation, have thought it their duty, first and foremost, to avoid anything that may be in the nature of a diplomatic blunder; for diplomatic blunders have consequences that are far reaching, and fall, in the main, on innocent people and upon generations who are perfectly innocent of the complications through which they are made to suffer.

As representative of the Government of India, it behoves me, also, to walk warily where there are so many pitfalls, and to avoid anything which may be in the nature of added bitterness, for bitterness there is in abundance in all conscience, and if one desires to cure one cannot start by making the disease worse.

As it turned out, during the two odd, staggered years that Srinvasa Sastri spent in South Africa — first when he arrived there in December 1926 as a member of the Habibullah Delegation which was sent from India to negotiate and study the position and grievances of the Indian community living there. The delegation was officially led by Sir Mohammad Habibullah, a member of the Viceroy’s Executive Council. The delegation was organized after rising tensions and discriminatory laws against Indians in South Africa, notably policies restricting Indian immigration and civil rights. Its purpose was to conduct on-the-ground investigations, negotiate with South African authorities, and seek a diplomatic solution to the discrimination faced by the Indian minority, without explicitly endorsing “repatriation” (return of Indians to India), which South Africa favored.

Although led by Habibullah in title, V. S. Srinivasa Sastri emerged as the main spokesperson and negotiator for Indian interests during the mission, owing to his diplomatic skill and reputation.

Then again when Sastri returned to South Africa in June 1927 to work as the Agent-General to the Government of India until January, 1929), the work he did for the Indian Community and for the British Crown earned him effusive encomiums from both!

How did Sastri pull it off?

(to be continued)

Sudarshan Madabushi